“Dreams are the stuff life is made of.” With those words, Roper Mountain Science Center’s director Darrell Harrison described the spirit that inspired the creation of the Symmes Hall of Science and its Health Education Center.

The story of Symmes Hall is one of imagination, collaboration, and determination. It represents what can happen when educators, healthcare professionals, and citizens unite around a shared purpose—to nurture curiosity and inspire healthier, more informed lives.

A Dream Takes Shape

In the late 1970s, the Greenville County Medical Society Auxiliary began to imagine a new kind of learning experience for children. The members of this volunteer organization, composed of local physicians’ spouses, wanted to give young people the opportunity to explore health and the human body in a setting filled with energy and discovery. Their vision was to move health education from printed materials into an environment where students could see, touch, and experience the science of wellness for themselves.

Realizing this dream required years of advocacy and effort. Funding, exhibit design, and operational planning all posed challenges, yet the Auxiliary’s passion inspired broad community support. Physicians, dentists, businesses, and foundations across Greenville County joined the cause. Together, they raised nearly $700,000 for exhibits and an additional $1.5 million for construction. The Greenville County School District partnered by providing staff and operating funds. Through shared purpose, the dream began to take physical form.

From Vision to Reality

By the spring of 1988, Symmes Hall of Science was ready to welcome its first exhibits. On May 16, 1988, trucks from Richard Rush Studios arrived from Chicago carrying the carefully designed displays that would become the centerpiece of Roper Mountain’s new Health Education Center.

Richard Rush was a pioneer in exhibit design and one of the most respected figures in health education interpretation. A sculptor, designer, and innovator, Rush specialized in creating life-sized anatomical models that combined art and science to make complex ideas accessible to learners of all ages. His work could be found in museums, science centers, and medical institutions across the country.

Perhaps his most famous creation was TAM—the Transparent Anatomical Model. First developed in the 1950s, TAM was a life-sized, illuminated model that revealed the major organs and systems of the human body in vivid detail. TAM’s ability to “come alive” through synchronized lights and narration captured the imagination of millions of visitors across the world. By the time Roper Mountain received its own TAM, the model had already become an icon of public health education, representing the perfect blend of artistry, technology, and learning.

When Rush’s exhibits arrived at Roper Mountain, the dream of the Greenville County Medical Society Auxiliary finally took on a tangible form. Symmes Hall of Science now had the centerpiece that would inspire generations.

The Health Education Center officially opened on September 15, 1988. The event featured keynote speaker Dr. Kenneth H. Cooper, known globally as the “Father of Aerobics.” His remarks emphasized the importance of preventive health, physical fitness, and lifelong wellness, perfectly reflecting the new center’s mission.

An Immersive Approach to Health Education

When students entered the Health Education Center, they stepped into a world designed to engage every sense. The space featured five themed classrooms, each focusing on a different aspect of health and human biology:

- Dental Health: A giant set of teeth and gums helped students learn proper brushing and hygiene habits.

- Nutrition: Interactive displays demonstrated how food choices affected energy, growth, and long-term health.

- General Anatomy: Detailed models and simulations encouraged students to explore how organs and systems work together.

- Life Begins: An age-appropriate introduction to human development and growth, inspiring appreciation for the miracle of life.

- Drug Awareness: Clear, evidence-based lessons on how drugs and alcohol influence the body and mind, helping students make informed choices.

At the center of these exhibits stood TAM, the Transparent Anatomical Model. Students gathered around the glowing figure as lights illuminated the heart, lungs, brain, and circulatory system. The voice that accompanied the display explained how the body’s parts worked in harmony. For many young visitors, TAM was their first introduction to human anatomy and a memorable symbol of the wonder of science.

Each lesson within the Health Education Center was designed to foster curiosity and self-awareness. The programs helped children connect scientific understanding to their daily lives and encouraged them to take responsibility for their health.

A Generation of Learning and Wellness

For more than 25 years, the Health Education Center played a vital role in shaping how Greenville County students learned about health and wellness. Long before state standards required such instruction, Roper Mountain’s programs helped students understand the importance of nutrition, fitness, and personal responsibility.

Teachers praised the Center for bringing health concepts to life in a way that students could truly understand. Parents noticed their children returning home eager to share what they had learned and motivated to make better choices. The lessons reached beyond the classroom, influencing families and the broader community.

Evolution and Enduring Legacy

As educational needs evolved and health instruction became more integrated into school curricula, the Symmes Hall of Science transitioned to serve new purposes. The building was reconfigured to host a wider range of science programs, continuing to nurture curiosity and inquiry among students.

Although the original Health Education Center no longer operates in its original form, its influence remains visible in the lives it touched. Generations remember standing before TAM, exploring the interactive exhibits, and discovering the importance of taking care of themselves. Those memories continue to shape their perspectives on health, science, and the value of lifelong learning.

A Lasting Tribute to Shared Vision

The creation of the Health Education Center represents a remarkable chapter in Roper Mountain’s history. It stands as a tribute to the power of community partnership and shared vision.

The collaboration between the Greenville County Medical Society Auxiliary, the School District, and innovators like Richard Rush demonstrates how creativity and commitment can turn an idea into a legacy that benefits generations.

Today, Symmes Hall of Science continues to serve as a symbol of what is possible when imagination, education, and community come together and reminds us that every great achievement begins with a dream, and that when dreams are nurtured, they can shape the future for all who follow.

With the Tricentennial Celebration over and the Parks, Recreation, and Tourism Commission lacking the budget to successfully reopen the park, Governor John West began looking outside traditional channels for a solution. One of the people he reached out to in the Greenville community during the early summer of 1971 was Dr. Floyd J. Hall, Superintendent of Greenville County School District. Governor West explained that the PRT did not have the funds to operate the park and that “really, there was nothing on the mountain to attract tourists.” Restrictions in the deed prohibited the type of development that could have drawn visitors, which was disappointing given the original high hopes that the site would become one of the Upstate’s “must-see” destinations. Instead, the land had become an economic burden for the state.

With the Tricentennial Celebration over and the Parks, Recreation, and Tourism Commission lacking the budget to successfully reopen the park, Governor John West began looking outside traditional channels for a solution. One of the people he reached out to in the Greenville community during the early summer of 1971 was Dr. Floyd J. Hall, Superintendent of Greenville County School District. Governor West explained that the PRT did not have the funds to operate the park and that “really, there was nothing on the mountain to attract tourists.” Restrictions in the deed prohibited the type of development that could have drawn visitors, which was disappointing given the original high hopes that the site would become one of the Upstate’s “must-see” destinations. Instead, the land had become an economic burden for the state. On November 13, 1973, the trustees of the Greenville County Schools board received a formal briefing from Brice Latham, an environmental science consultant, outlining potential plans for an environmental science center on Roper Mountain. His presentation included recommendations for programming, staffing, and cost estimates. The proposal was well received, and the board voted to authorize Dr. Hall to formally request that the Department of Parks, Recreation, and Tourism deed the 62-acre site to the school district for use as a science center.

On November 13, 1973, the trustees of the Greenville County Schools board received a formal briefing from Brice Latham, an environmental science consultant, outlining potential plans for an environmental science center on Roper Mountain. His presentation included recommendations for programming, staffing, and cost estimates. The proposal was well received, and the board voted to authorize Dr. Hall to formally request that the Department of Parks, Recreation, and Tourism deed the 62-acre site to the school district for use as a science center. Sampling of Preliminary Artifacts Recovered from RMSC Site

Sampling of Preliminary Artifacts Recovered from RMSC Site Sampling of 1882 Kyzer Map of Greenville County

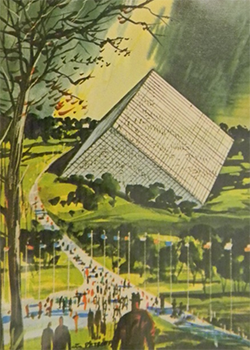

Sampling of 1882 Kyzer Map of Greenville County A GRAND VISION OF ROPER MOUNTAIN

A GRAND VISION OF ROPER MOUNTAIN THE TETRON

THE TETRON This floor also highlighted South Carolina’s advancements in power and energy. Displays demonstrated the state’s leadership in hydroelectric, steam turbine, and nuclear power generation. Anderson, South Carolina, was featured prominently as the first all-electric city in the South, while the nearby Keowee-Toxaway Nuclear Power Station symbolized the cutting-edge potential of the “world of tomorrow.”

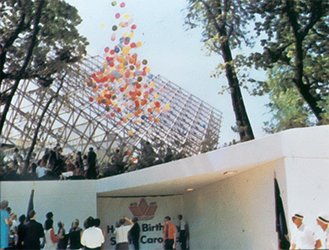

This floor also highlighted South Carolina’s advancements in power and energy. Displays demonstrated the state’s leadership in hydroelectric, steam turbine, and nuclear power generation. Anderson, South Carolina, was featured prominently as the first all-electric city in the South, while the nearby Keowee-Toxaway Nuclear Power Station symbolized the cutting-edge potential of the “world of tomorrow.” A MEMORABLE OPENING AMIDST CHALLENGES

A MEMORABLE OPENING AMIDST CHALLENGES Lobby of the Piedmont Exposition Center on Opening Day, July 4, 1970

Lobby of the Piedmont Exposition Center on Opening Day, July 4, 1970

Crowds entering the Piedmont Exposition Center through the Gateway Tunnel, part of which remains today.

Crowds entering the Piedmont Exposition Center through the Gateway Tunnel, part of which remains today.

Governor Robert McNair and Buckminster Fuller at the unveiling of the Tetron model

Governor Robert McNair and Buckminster Fuller at the unveiling of the Tetron model

The Tetron under construction in early 1970

The Tetron under construction in early 1970